How did we go from Dante and Flannery O’Conner, from Dostoyevsky and Da Vinci, to this barren, desolate landscape of Christian art? How did we get from Bach and Handel, from early twentieth century American Gospel music, to the travesty of modern Christian country-rock and the cringe inducing mediocrity of post-conciliar Catholic liturgical music? Where did Christian devotional art jump the proverbial shark? Somewhere along the line the arts lost their religion, and religion lost its art. Art and music became institutionalized; a part of the academy, indoctrinated into Enlightenment values, and suspicious of the value of enlightenment. Nihilism replaced the Good, the True and the Beautiful and the Theory of Relativity replaced the prologue to the Gospel of John. In the Catholic universe specifically, we lost our faith. Catholicism in the pre-conciliar period was already losing its hold on the artist. The neocon legalism of the Neo-Scholastics had eclipsed the cosmic, Neoplatonic understanding of the early Church Fathers and the poetic speculations of the medieval mystics. The pre-conciliar Church was a Church of banned books and ridiculous formulations: “learn this prayer and get ten days off of purgatory.” No thinker—no artist—could take such nonsense seriously. The Church as spiritual institution had become a mental institution.

Then came Vatican II and the great hope of renewal, the great challenge of tackling modernity head on, of engaging with the culture and its ideas from a Catholic worldview; not of modernizing the Church but of meeting the challenges posed by the post-Enlightenment atheistic paradigm with a better Way, a richer Philosophy of Being, a more compelling worldview. That was the idea. A return to source. A revival of the religion via the Church Fathers. A little less Aristotle and a little more Plato. Instead, the modernists in the Church hijacked the post-conciliar period and went about liberalizing and secularizing the Catholic Church to such an extent that it lost its very essence, its meaning. Since we no longer had to abstain from meat on Fridays, it followed that we no longer had to take Lent seriously, we no longer had to discipline ourselves, to steel ourselves against modernity’s excesses. We no longer had to take the Catholic faith seriously. We could eat meat whenever we damn well pleased and go on a second vacation this year. We could go to a fancy dinner on Friday, take the boat to the lake on Saturday, and catch 11am Mass on Sunday. With a crisis of meaning in the culture at large, we were responding by making Catholicism ever more meaningless. Instead of rising to the challenge of modernity by offering a real alternative, we were allowing modernity to dictate the terms. No small wonder we lost the artists. No small wonder we haven’t seen great Catholic art in the post-conciliar period. Artists deal in meaning, and if you are going to strip meaning from the Church, then the result will be (and has been) to strip the Church of art.

But, there is always hope. We are Christians, after all, and hope is still one of our three cardinal virtues. Mainstream culture, birthed by modernity’s Cartesian values, is in serious crisis. We have stripped the world of its center. We have separated logic from logos, and the wheels on the post-enlightenment Western worldview are falling off. The bloom is off the secular rose and there is not enough lipstick in the world to pretty up this pig. Left and Right have lost their sense of direction. The American anti-war movement is on life support and fading fast. Boys think they are girls and girls want to be boys and you dare not question this phenomena for fear of being accused of a lack of sensitivity—or worse. The cities have become hotbeds of conformity catering exclusively to young professionals, and outside of the cities the suburbs are violently crumbling. Boomer retirees have colonized the small towns, pushing the cost of living beyond the reach of a shrinking working class, and on the edges of everywhere the homeless, unhoused masses wander aimlessly in drug-zombie stupor through this post-apocalyptic American Nightmare. And therein lies the hope. We are at an undeniable crossroads as a society. The dark house of cards that we have built our institutions on is being exposed, brought into the light of day, and there will be no political salvation.

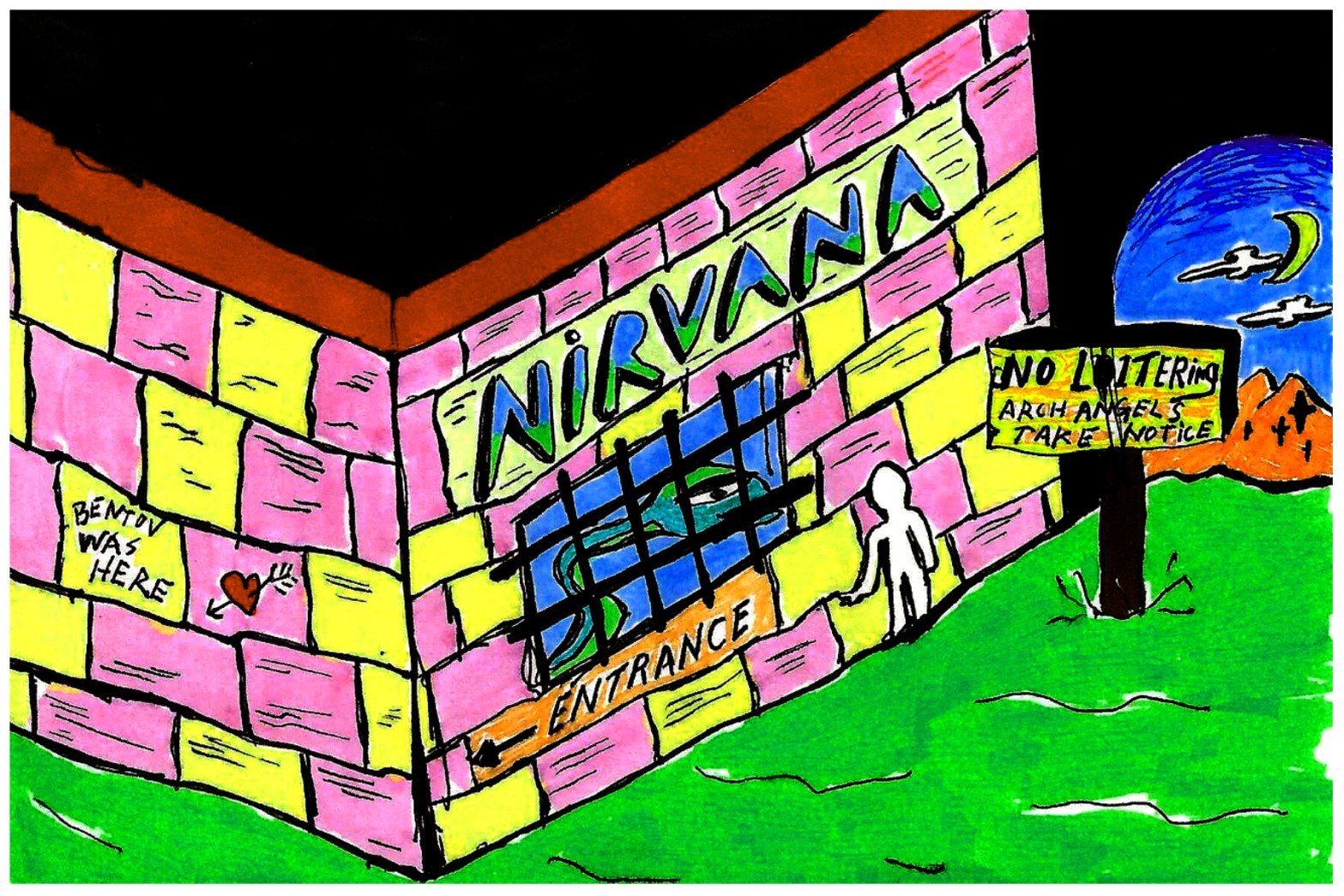

There is no salvation in politics. There is only salvation in Truth, and Truth has a shape—its shape is cruciform: a vertical bar connecting humanity to God, and a horizontal bar connecting us to each other. And artists, true artists, are always after the Truth. Great art is never atheistic. To the extent that the secular world has produced great art, it has been, however unknowingly, in relationship to the Unknown God; a God who is, nevertheless, always reaching down to reveal himself to us. As George Steiner argues in his book Real Presences, a transcendent reality grounds all genuine art, and as Hans Urs von Balthasar points out in Christian Meditation, “…the senses and imagination of a believer…become of themselves ‘spiritual’ senses and a ‘spiritual’ imagination, since they are at the service of faith, and together with their ‘object’—the man Jesus Christ, who is open to God and reveals God—they in turn open up to the divine.” The Unknown God is knowable, the Father reaches for his children in infinite friendship, and the principalities and powers of this world are powerless in the face of Eternity. But bourgeois Christianity; ornamental, devoid of Spirit, and atheistic in its presentation — is in no position to inspire, to evangelize, and to rise to the challenges we face as a society. We need a mystical, tactile, all-encompassing Christianity. Christianity as an Art. And who better to articulate this vision of a robust and colorful Christianity than the artists? Perhaps a new generation of Christian artists will emerge, pick up their parable, and show us the way. I have faith in our artists, and I hope that it happens, because I would love to see it.